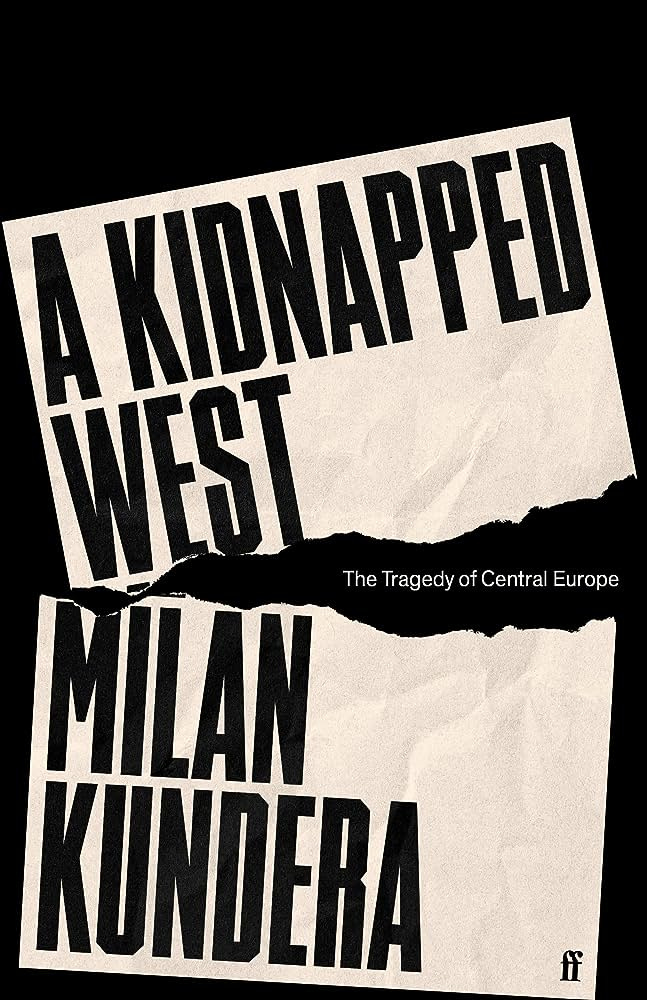

A Kidnapped West: The Tragedy of Central Europe by Milan Kundera

The text that reshaped the mental map of Europe in 1983

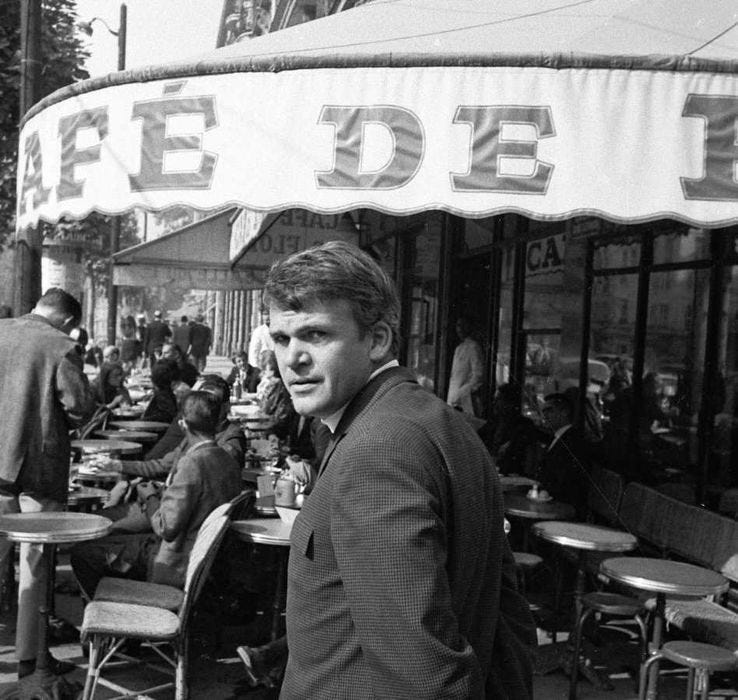

Milan Kundera (1929 - 2023) was a Czech-French novelist. Kundera went into exile in France in 1975, acquiring citizenship in 1981. Kundera's best-known work is The Unbearable Lightness of Being. He wrote A Kidnapped West in 1983, when Czechoslovakia was under the yoke of soviet dictatorship.

Back cover:

The people of Central Europe cannot be separated from European history; they cannot exist outside it; but they represent the wrong side of this history; they are its victims and outsiders.

In a moment of historic peril and uncertainty in mainland Europe, Milan Kundera makes the case for Central Europe as the nucleus of European values and as a lightning rod for its potential dangers.

For the countries that make up this region where democracy is under continued threat from Russian oppression, language and culture play an active role in affirming national identity. And each of these countries - Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia - has been historically overlooked by the major powers of Western Europe. But Kundera cautions that this blindness puts Europe's cultural and political independence at risk, a warning that feels increasingly relevant to our current moment, and our future.

Reading notes

Main take-away: Central Europe belongs to the West.

Introduction

A Kidnapped West is an article by Milan Kundera published in Le Débat in 1983. It provoked a wave of reactions throughout Central Europe. It "reshaped the mental map of Europe".

At a time when the West saw Central Europe as part of the Eastern bloc, Kundera reminds us that Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia belong to the West, and that culture is the sanctuary of these countries' identity.

Russian tanks enter Budapest in 1956. The last dispatch from the head of the Hungarian press agency: "We will die for Hungary and Europe". His building was bombed by the Russians immediately afterwards.

Central Europe, a victim of history

Geographical Europe (from the Atlantic to the Urals) has always been divided into two parts:

one linked to ancient Rome and the Catholic Church

the other rooted in Byzantium and the Orthodox Church.

In 1945, the border between these two Europeans shifted a few hundred km to the west. Nations that had always considered themselves Western awoke in the East. This gave rise to 3 basic situations: Western Europe, Central Europe and Eastern Europe.

Polish revolts of 1956, 1968, 1970. Prague uprising 1968. Hungarian uprising 1956. Bulgaria did not revolt, as it was part of Orthodox Europe from the outset.

Paradoxically, the period after 1945 was both the most tragic and one of the greatest in its cultural history. Under threat, cultural life intensified. Kundera writes: "the profound meaning of their resistance is the defense of their identity; or in other words, the defense of their Westernness", in the face of Soviet acculturation.

The most beautiful and lucid text on Russia is Russia and The Virus of Freedom by Emil Cioran in History and Utopia: "Everything about her is vertiginous, awful, elusive". For thousands of years, the Czechs have had no contact with Russia, despite their linguistic kinship. The relationship between Russia and Poland is a struggle to the death.

Kundera writes: "I want to emphasize once again that it is on the eastern frontier of the West that, better than anywhere else, Russia is perceived as an Anti-West; it appears not only as one of the European powers among others, but as a particular civilization, as another civilization."

The peoples of Central Europe: victims of history. In this disenchanted historical experience lies the source of their cultural originality, their non-serious spirit, which scoffs at grandeur and glory. The disappearance of the Central European cultural heartland is the greatest event of the century for Western civilization. Europe didn't notice the disappearance because it didn't feel its cultural unity. In the Middle Ages, Europe's unity was based on religion.