These weird Westerners

How the West Became Psychologically Different and Shaped the Modern World

Dear readers,

in this edition of Why the West, I wanted to share a recent read that particularly struck me: The Weirdest People in the World by Joseph Henrich, an American anthropologist and professor at Harvard.

He delves into a question that has intrigued me for years: why did Europe, from the 16th century, begin an economic and technological boom unprecedented in the history of humanity? According to the author, it's primarily a story of mentality: Westerners have developed a particular psychology that is at the root of their economic and scientific success.

Let's take a closer look.

A Universalist and Individualist Mentality

The book opens with a university study called "The Passenger's Dilemma." Imagine you're in a friend's car. He is speeding well above the limit and, unable to brake in time, hit a pedestrian. Following the accident, the police arrest him. If you lie and testify that he was driving within the speed limit, he avoids prison. What would you do?

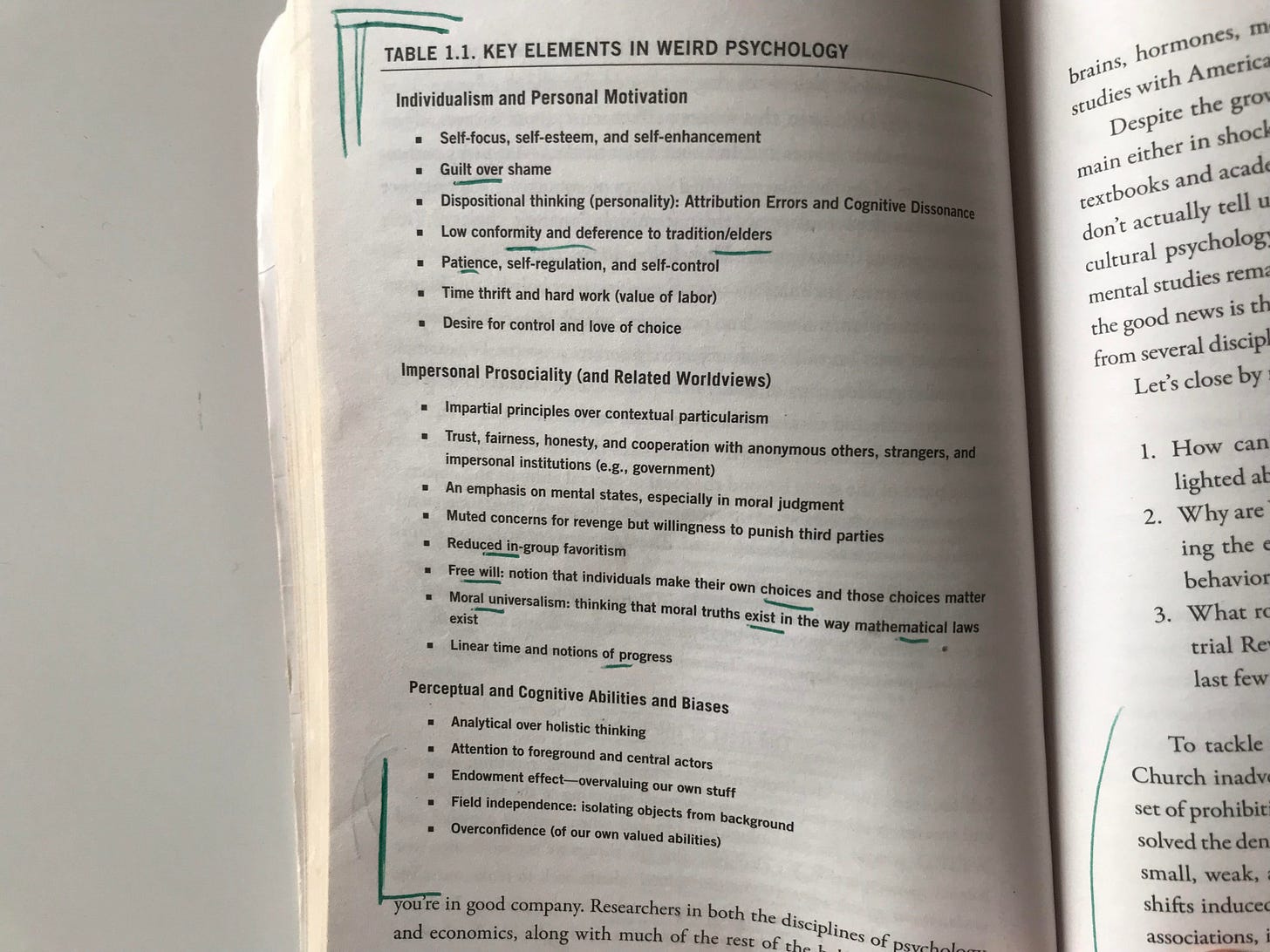

Westerners respond very differently from other cultures. In the United States, Australia, Norway, or Switzerland, 90% of participants refuse to lie to spare their friend from prison. Overall, this rate exceeds 80% in all Western countries. This result reflects a commitment to universal rules and the value of impartiality, even at the expense of friendship or family ties. These results contrast with the rest of the world: in China, Venezuela, or South Korea, over 50% of participants agree to testify and thus lie to spare their friend from prison. The author summarizes this difference in mentality with a well-phrased formula: "What we call favoritism, others call solidarity."

The anthropologist highlights another study underscoring the unique mentality of Westerners. When asked to complete the sentence "I am ...," they are much more likely than others to respond with a personal attribute ("I am a professor," "I am an athlete"). Conversely, participants from other civilizations are more inclined to respond with their place in the family structure ("I am the brother of...", "I am the daughter of..."). I personally experienced this in India, where you are often asked, "Are you married?" before being asked, "What do you do for a living?"

Finally, the author shows that Westerners are more likely to feel guilt than shame, whereas it's the opposite in other civilizations. Guilt is a private emotion triggered by falling short of our own expectations; shame arises from not meeting the expectations of one's community.

So why such differences between the psychology of Westerners and that of other civilizations?

The Origins of a Very Distinct Mentality

The anthropologist illustrates that Westerners have developed a unique psychology over the past two millennia: the clan or tribal mentality, which is the "normal" organization of human societies, has gradually given way to a more individualistic, universal, and impartial mentality. Henrich adds that from an anthropological standpoint, this Western mentality is very peculiar WEIRD (the acronym for Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic ) has nothing natural about it: humans spontaneously and normally have a clan mentality, based on strong family ties, and not on individuality or impartiality.

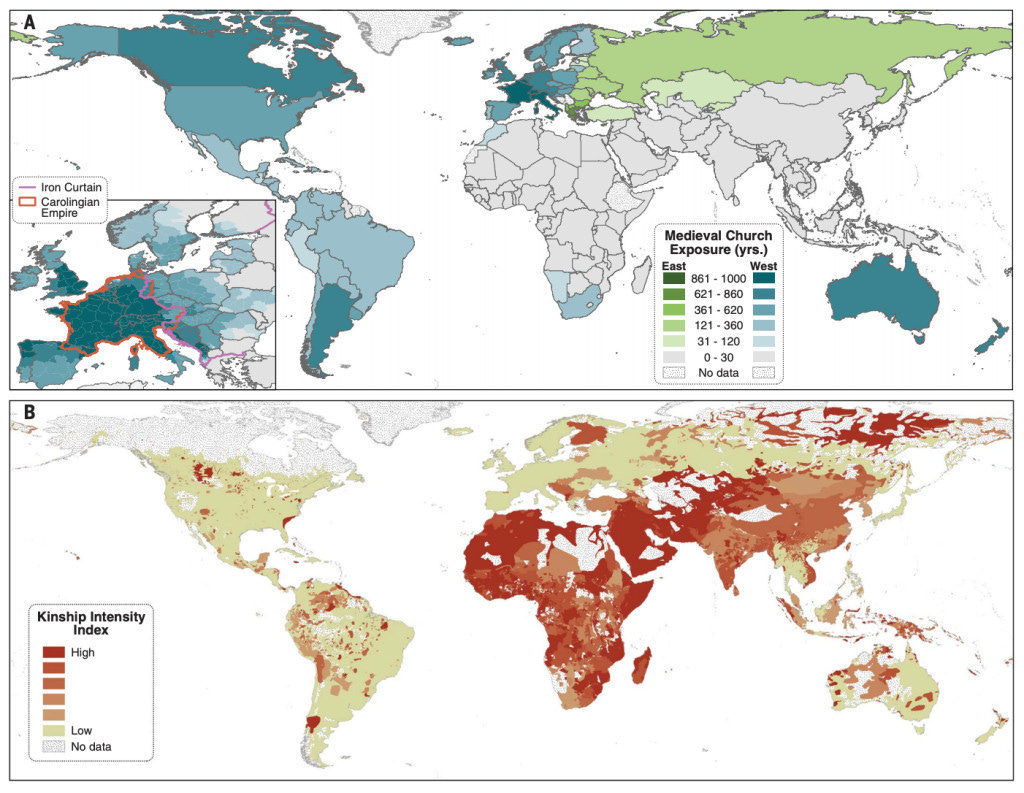

According to Joseph Henrich, the origins of this particular mentality can be traced back to the religious history of the West. From the 4th century onwards, the Catholic Church began to prohibit marriages between increasingly distant cousins. For instance, in 1050, when William the Conqueror wanted to marry his fifth cousin, Pope Leo IX opposed it in accordance with the rule prohibiting consanguineous marriages up to the seventh degree of kinship. By weakening extended kinship ties, the Church fostered the emergence of voluntary associations and contractual institutions —non-familial or non-clan-based— such as guilds, monasteries (I've written here or here about their fundamental role in Europe's economic development), free cities, universities, businesses, and so forth. This mentality gradually facilitated the rise of social mobility, individualism, and the advent of the rule of law. Societies that guarantee more freedom to their members tend to be more prosperous, and these developments favored economic development.

Thus, through the imposition of increasingly strict rules regarding cousin marriages, the Church unintentionally promoted the emergence in Europe of a weird but more open mentality built upon universally applicable laws, breaking away from the "normal" mentality of human societies based on kinship and blood ties.

The Consequences of a Very Distinct Mentality

While they may not always make good friends when it comes to lying to the police, Westerners are more inclined than others to trust people outside their close circle (see map above) or to donate blood. It's a self-perpetuating phenomenon: the emergence of institutions based on individual freedom, in turn, favored individualistic, universalist, and impartial mentalities. Joseph Henrich sees in this virtuous circle one of the factors in the consolidation of democracy in the West.

Henrich also demonstrates that this mentality stimulated innovation in Europe, as individuals were more willing to share their ideas and collaborate with people outside their family circle. The Industrial Revolution and modern science were born out of the scientific and intellectual emulation sweeping across Europe since the Renaissance.

The author also notes that Japan, China, or Korea, eager to catch up economically with the West, successfully "copied and pasted" certain rules and institutions that they identified as fundamental to building a prosperous country. The rules these countries adopted are precisely those that, over the centuries, had materialized this particular mentality in the legal systems of Western countries. Thus, starting from the 1880s, Japan implemented a civil code inspired by that of Germany and France. In China, in the 1950s, the Communist Party launched a program to abolish clans, arranged marriages, and inheritance inequalities between daughters and sons. In 1957, South Korea introduced a Western-style civil code prohibiting marriages between cousins up to the third degree and requiring the consent of the future spouses.

If you're interested in the rise of Europe, I recommend this article on a book that complements Henrich's work:

Let's Summarize.

For the anthropologist, the gradual prohibition by the Church of marriage between increasingly distant degrees of kinship removed Westerners from a clan-based mentality and dissolved institutions based on blood ties, which fostered trust among non-family-related individuals and allowed for the emergence of individualistic and innovative societies, based on the rule of law and individual freedom. These conditions facilitated the economic and scientific development of Europe.

Henrich shows us that mentalities play a crucial but often overlooked role in the history of civilization development. They are, for him, the dark matter of history. He deliberately adopts this term from astrophysics, referring to those components of the universe that science struggles to explain, such as black holes. If the industrial revolution emerged in Europe, it wasn't because we had more coal or more fertile fields, but because Europeans had the mentality conducive to innovation. This idea echoes that of American historian David S. Landes: in his seminal work The Wealth and Poverty of Nations (1996), he explains Europe's rise through a mentality favorable to innovation, which he called "the invention of invention."

Find all previous articles from Why the West on the homepage of the website. You can also follow me on X (ex-twitter).