About Napoleon

"Through his Code, his University and his prefects, Napoleon reigned in France until 1940"

A short announcement to start with: thank you for your very positive feedback on my conversation with the Lithuanian ambassador. I'll be doing interviews more regularly in the future.

Dear Readers,

special issue this week. As you may know, Ridley Scott's film about Napoleon is released on Wednesday. And since I’m French, it is my national duty to go and see it.

On a more serious note, I've often come across opinions and remarks about Napoleon in my readings. In this article, I wanted to bring together the ones I found most interesting. You'll come across historians, writers and politicians. But first, I'll give us a brief biography of Napoleon to refresh our memory.

Short biography of Napoleon

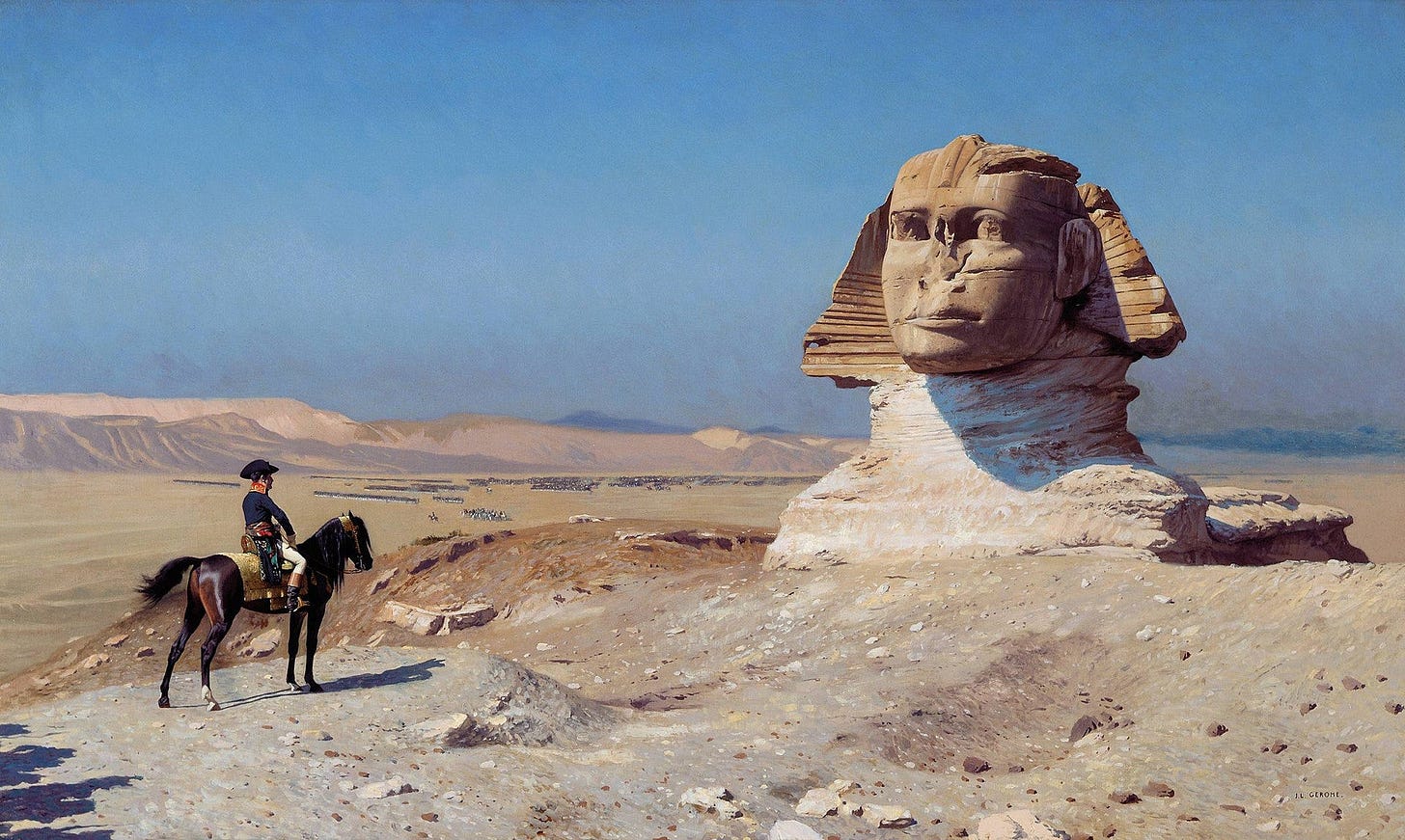

Napoleon Bonaparte was born on 15 August 1769 in Ajaccio. He began a military career and quickly rose through the ranks during the French Revolution. After the Italian and Egyptian campaigns, he overthrew the Directoire government in 1799 in the coup d'état of 18 Brumaire and took power as First Consul. He consolidated the achievements of the Revolution, such as equality before the law, and launched major reforms, including the creation of the Banque de France, prefects, lycée and Napoleonic code.

In 1804, Napoleon crowned himself Emperor of the French, marking the beginning of the French Empire. Facing a coalition led by Great Britain, the Grande Armée began its conquest of Europe, of which the famous victory at Austerlitz in 1805 is one of the symbols (here a great video explaining this military masterpiece).

However, the campaigns in Spain in 1808 and especially Russia in 1812 marked the beginning of his downfall. After his defeat at the Battle of Leipzig in 1813, Napoleon was exiled to Elba island in 1814. He managed to escape and briefly returned to power during the Hundred Days in 1815, but was finally defeated at the Battle of Waterloo, which put a definitive end to his reign. The deposed emperor was exiled to the island of St Helena in the South Atlantic Ocean, where he spent the last years of his life and dictated his memoirs. He died on 5 May 1821.

Considerations on Napoleon

I chose Charles de Gaulle, Georges Pompidou, René Grousset and Jacques Bainville because I found their reflections on the Napoleonic era particularly instructive.

Georges Pompidou, President of France (1969 - 1974)

In August 1969, George Pompidou, who had just been elected President of France, traveled to Ajaccio in Corsica to celebrate the bicentenary of Napoleon's birth. He gave a speech in which he declared:

"The genius of Napoleon dominates our history just as he prefigures the future of Europe. It is to him that we owe most of the institutions which, over the centuries and despite the necessary changes, still form the backbone of our country. (...) Napoleon did not find happiness and he did not give it to France. But, in the absence of happiness, he reached the heights of greatness and filled France with it, to such an extent that since then our people have never resigned themselves to mediocrity and have always answered the call of honour".

This statement by Georges Pompidou should be read in conjunction with his own epitaph, written just after his election as President of France: "Happy people have no history, and I hope that historians will not have too much to say about my term of office". Breaking with Napoleon's quest for glory, Pompidou preferred to anchor his political action in a quiet quest for happiness, in line with the aspirations of the Trente Glorieuses.

René Grousset, Historian

René Grousset is one of my favorite historians. Died in 1952, he was a member of the Académie française and chief curator of the National Museum of Asian Arts in Paris (or Musée Guimet). In 1949, he wrote Figures de Proue in which he retraced the lives of several great historical figures such as Caesar, Charlemagne and Bismarck. One chapter is dedicated to Napoleon: the historian is not kind to the emperor. While he praises the statesman Bonaparte - "through his Code, his University, his prefects, Napoleon reigned in France until 1940" - he is highly critical of the conqueror: he criticises him for his romanticism and his great epics, which ultimately weakened France. Just as the country was emerging from a decade of revolutionary turmoil (1789 - 1799) and yearning for stability, Napoleon imposed a decade of war (1805 - 1815): "France was coming into port. He seized the ship and threw it back on the high seas". For Grousset, this thirst for conquest probably stemmed from his overly classical and Latin training: all his life, Bonaparte wanted to remake the Roman Empire. In this sense, Napoleon was very much a man of his time, obsessed with the Roman and Greek heritage. "We were brought up in schools of Rome and Athens" wrote the revolutionary Camille Desmoulins about the education he received at college (on this subject, see my article At the origins of Western Civilisation).

Jacques Bainville, historian

Jacques Bainville was a French historian and journalist best known for his Histoire de France, written in 1924 and still widely read today, and for The Political Consequences of Peace, a premonitory work published in 1920 in which he predicted the downward spiral leading to the Second World War. He also wrote a biography of Napoleon in 1931 in which he showed his admiration for the genius of the military strategist Bonaparte but deplored the megalomania of the end of the reign which erased the conquests and achievements of the beginning, i.e. the stabilisation of French society after the Revolution. Bainville wrote:

"Except for glory, except for art, it would probably have been better if he had not existed."

He uses a phrase that Napoleon is said to have uttered when visiting the tomb of Rousseau, whose Social Contract inspired the French Revolution: "Time will tell whether it would not have been better, for the rest of the world, if neither Rousseau nor I had ever existed". Despite his reservations about the Napoleonic era, Bainville could only observe that "the magic of the name Napoleon is one of the most astonishing phenomena in the history of the French people".

Charles de Gaulle, President of France (1958 - 1969)

"What Napoleon did until 1808 was perfect"

This is what the General is said to have said to the writer André Malraux. In Les Chênes qu'on abat, Malraux recounts his discussions with a de Gaulle at the end of his life, retired to his house in Eastern France. They talked about history, politics and literature. De Gaulle admired Napoleon but reproached him for the excesses that led to his final downfall. He should have been content with his initial successes. Like Napoleon, de Gaulle was a soldier who restored a national unity after a period of great turmoil. Like Napoleon, de Gaulle left an institutional legacy that has spanned the decades with his Fifth Republic. However, by resigning after a lost referendum, de Gaulle accepted to leave the office.

These two historical figures left France with historical epics to cling to. As historian Patrice Gueniffey explains: "Napoleon and de Gaulle left an even more important intangible legacy: a source of collective pride, a model of political efficiency, an example of courage, an illustration of the powers of the will and, with Napoleon's final failure, a philosophical lesson on the 'measure' essential to the government of men". More fundamentally, they gave unity to a country that initially lacked it. Unlike Germany, which shared a common language and culture even before it was unified by Bismarck, regions and cities as different as Flemish-speaking Dunkirk, German-speaking Strasbourg, Italian-speaking Nice, Catalan-speaking Perpignan and Occitan-speaking Toulouse had, a priori, no common destiny. As Patrice Gueniffey writes, "France cannot do without great men or heroes, any more than it can do without a strong state. They represent its unfindable unity". Before the Revolution, it was the king who played this unifying role. Afterwards, it was the State and the "great men" who took over.

Conclusion

Although they admired his initial successes and his administrative work, they all criticised him for his hubris. Napoleon was "defeated by his conquest", wrote Victor Hugo about the Russian campaign. His disproportionate ambition led to his downfall. The paradox is that it is this same overweening ambition that explains why he did not remain an anonymous lieutenant but became an extraordinary historical figure who we are still talking about two centuries after his death. He saw himself as a meteorite, and France was the tool with which he built his epic. He once wrote to his wife Joséphine: "I haven't had a cup of tea without cursing the glory and ambition that keep me away from the soul of my life".

So what are we to make of Napoleon's adventure? Let's leave the last word to Charles de Gaulle.

- “Where do you stand with the Emperor?” the writer André Malraux asked the General during a conversation a few months before his death.

- “A very great mind, and a rather small soul (...) He left France smaller than he had found it, that's fine; but a nation cannot be defined like that. For France, he had to exist. It's a bit like Versailles: it had to be done. (...) Just look at how little Napoleon's glory has suffered as a result of his defeats. Look at the power of his name, not just for the French. It stirs souls. Let's not bargain greatness”.

Find all the articles on the Why the West home page.