"They tried to erase our identity": conversation with the Lithuanian ambassador to France

Small country, big history

Dear readers,

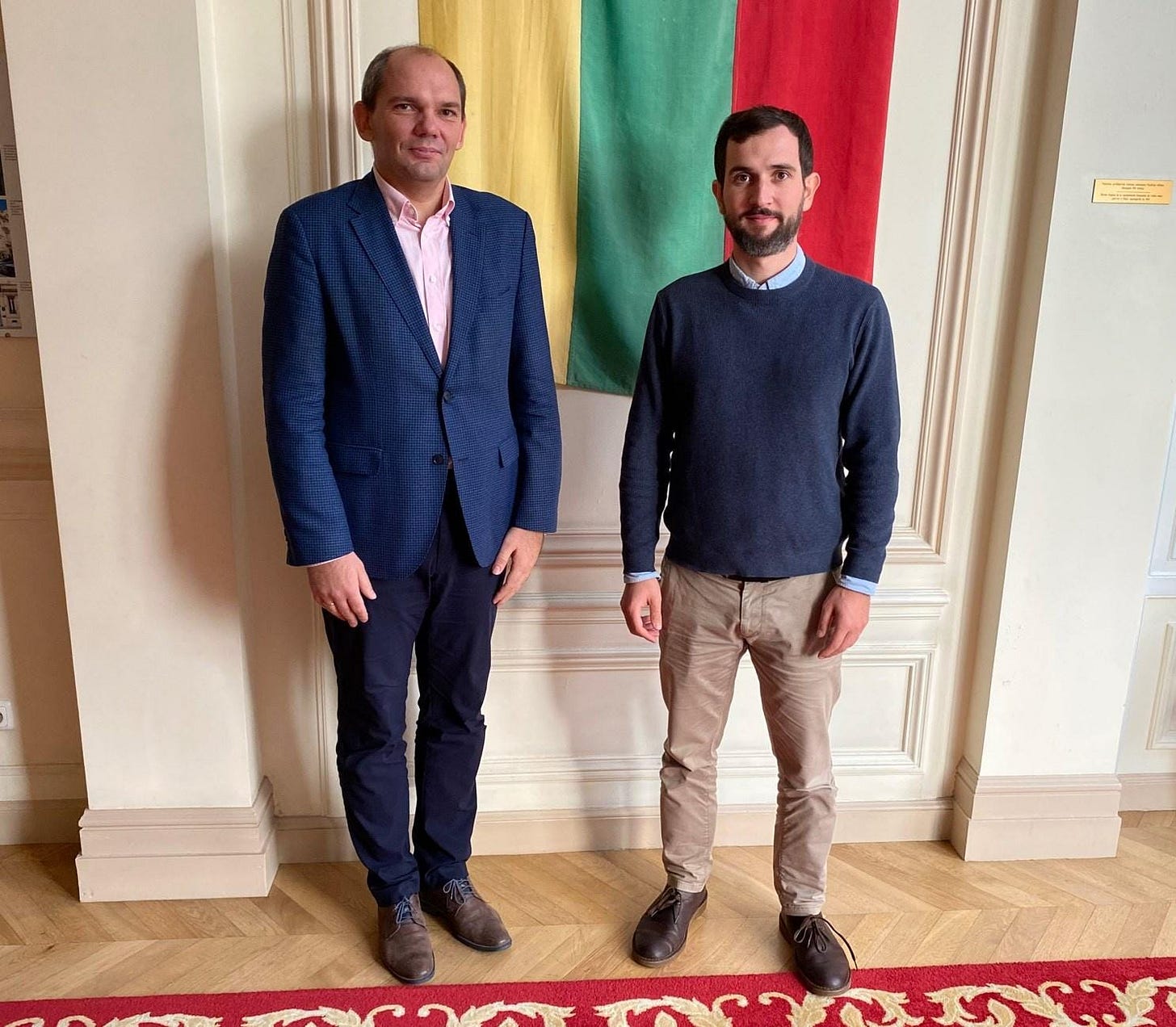

a few days ago I had the opportunity to interview Nerijus Aleksiejunas, Lithuania's ambassador to France since 2019. As a career diplomat, he was advisor to the President of Lithuania before arriving in Paris. I had previously met the ambassador at an event where he was presenting Lithuania's foreign policy. I was intrigued by the voluntarism and particular history of this country which is little known. So I asked for a meeting to find out more.

During our conversation, which was punctuated by personal anecdotes, we covered a range of subjects that gave me a better understanding of Lithuania, its people and its history: the daily life under the Soviet occupation, the success of Vinted and NordVPN or the historical links with Ukraine. I also understood why Lithuania is so active on the diplomatic front, standing up to China and Russia.

This issue of Why the West is divided into two parts: before the interview with the ambassador, I will briefly introduce Lithuania and its history.

Lithuania, a small country with a big history

With a surface area of 65,000 km² (twice the size of Belgium) and a population of 2.8 million, Lithuania is the largest, most populous and most southerly of the three Baltic States. Its capital is Vilnius and the country shares borders with Latvia to the north, Belarus to the east, Poland to the south and Russia (Kaliningrad enclave) to the west. The population is predominantly Catholic, and the 2 largest foreign communities are Ukrainian and Belarusian. The country's economy is geared towards innovation: one of the best-known Lithuanian companies is Vinted, the most successful second-hand apparel app in Europe.

The name of the country appears for the first time in 1009. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania began to flourish in the 13th century. It reached its apogee in the 15th century, when it became the largest state in Europe, stretching from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea: its territory included present-day Lithuania and a large part of Belarus, Ukraine and Poland. This is an important factor, and we'll return to it later. The country has a tradition of openness: in 1323, the Grand Duke of Lithuania invited European craftsmen and merchants to settle in Vilnius and also offered protection to the Jews. The Lithuanian Jewish community represented 10% of the country's population and included the famous painter Marc Chagall and the philosopher Emmanuel Levinas. In the 16th century, Lithuania joined forces with Poland to form the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. At the end of the 18th century, the Russian Empire annexed Lithuania. Except for the interwar period (1918-1939), the country did not regain its sovereignty until the collapse of the USSR in 1990. Lithuania has been a member of the European Union since 2004, and the euro has been its currency since 2015.

What distinguishes Lithuania is its willingness to defend Western values. For example, the Baltic country has not hesitated to offend China by authorising Taiwan to open a representative office in Vilnius in 2021. And despite the Chinese economic boycott, Lithuania has no intention of going back on its decision. Lithuania is also the 2nd country in the world (behind wealthy Norway) that gives the most support to Ukraine in proportion to its GDP.

As a complement, I recommend this 12 minute video from the French TV show Behind the maps: Baltic Countries, at the gates of war (in French with English subtitles available).

Interview with Nerijus Aleksiejunas, Lithuanian Ambassador to France

Guillaume Gau: Despite its modest size, Lithuania is very active diplomatically and does not hesitate to confront major autocracies. Is there any historical explanation for this state of mind?

Nerijus Aleksiejunas: First of all, Lithuania has a long tradition of statehood and diplomacy. In the 15th century, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was the largest state in Europe: it was twice the size of today’s France. We have retained something of this "big country" mentality.

Recent history also explains this attitude. The end of the Second World War was not exactly synonymous with peace for Lithuanians: from 1940 to 1990, we suffered 5 decades of Soviet occupation. Until the end of the 1950s, Lithuanian resistance fighters fought against the Russian invaders: they were known as the Forest Brothers. They were hunted down by the KGB and took refuge in the dense Baltic forests. It wasn't until 1990 that we regained our independence. We know that freedom and democracy cannot be taken for granted: we have to fight to preserve them.

G.G. You were born in 1978, under Soviet occupation. In concrete terms, what does it mean to grow up in a country under a Communist dictatorship?

N.A. My family was devastated by Soviet oppression. From 1940 onwards, the Soviets deported thousands of Lithuanians to the Gulag in Siberia1. My grandfather was one of them: he never came back. He was deported 2 months before his son was born: my father never knew his father. My grandfather was deported because he was a civil servant: the Soviets wanted to behead the Lithuanian state.

In parallel with political repression, the Soviets tried to erase Lithuanian identity by rewriting history (the Grand Duchy of Lithuania disappeared from our history books) and doing everything they could to eradicate Christianity. For example, Christmas was a day like any other, not a public holiday. Displaying your religious beliefs could get you into trouble, so you had to be very discreet. But we have a long history and deep roots: 50 years of Soviet occupation were not enough to eradicate our identity.

On a daily basis, there were shortages and widespread corruption. For example, we were allowed 1 kg of bananas per person per year. I remember queuing for hours with my mother to get the precious bananas. Behind an egalitarian ideology, the injustices were blatant: the Soviet elite enjoyed privileges and knowing someone in a high position gave you a pass.

"We have a long history and deep roots: 50 years of Soviet occupation were not enough to eradicate our identity." Nerijus Aleksiejunas

The ambassador's remark reminded me of this quote from Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Soviet dissident and author of The Gulag Archipelago: "To destroy a people, you must first sever their roots".

G.G. You've been in France for 4 years. How do you see the country?

N.A. I love the geographical diversity of your country. Sea, mountains, countryside: you've got it all. I also like the differences between your regions. And contrary to the cliché, I don't think the country is all that centralised: your regional capitals are very dynamic. I travel around the country a lot and I find the French very welcoming. Lithuanians also appreciate French culture and the French way of life. Some of your great authors have a link with Lithuania, like Romain Gary (his famous novel: Promise at dawn) who was born in Vilnius.

On the economic front, you have a very dynamic technological ecosystem. Our country is also very innovation-oriented and France represents a major market for Lithuanian start-ups such as Vinted and NordVPN. Finally, Franco-Lithuanian relations are going well. For example, Lithuania has just purchased 18 French Caesar cannons to bolster its army.

G.G. Why does Lithuania support Ukraine so strongly?

N.A. We have to stop Putin, otherwise he will keep moving forward. We have to show him that we won't give in. For Lithuanians, helping Ukraine means defending Europe, freedom and democracy. What's more, this support doesn't just come from the government: the whole of Lithuanian society is mobilising to welcome Ukrainian refugee families or send medicines. For example, a citizens' fund has just raised €14 million to buy military radars for Ukraine.

Historically, we also have a very strong relationship with our Ukrainian brothers. Our two peoples are very closely linked: Ukraine represented a large part of the territory of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Cultural and economic exchanges between our 2 countries have been very strong for centuries.

G.G. As a wrap-up, would you have a Lithuanian book to recommend?

N.A. I recommend Vilnius Wilno Vilna by Kristina Sabaliauskaite, 3 short stories about the history and atmosphere of Vilnius. The title is composed of the Lithuanian, Polish and Yiddish names of the city. It is a great book to read before a visit to Vilnius. There's also Siberian Haiku, a comic book by Jurga Vilé and Lina Itagaki about the deportation of Lithuanians to the Soviet gulags. This book touched me because it talks about what happened to my grandfather.

I'd also like to take this opportunity to point out that 2024 will be the Year of Lithuania in France: hundreds of events will be organised across the country to introduce the French to our culture and history.

G.G. Thank you for this conversation, Mr Ambassador!

N.A. You are welcome. Come and visit our country, we know how to welcome people!

Find all the articles on Why the West home page.

Between 1940 and 1955, an estimated 200,000 Lithuanians - almost 10% of the population - were deported to the Soviet gulags.