The world seen from Delhi

The Indians aim to make up for lost time

Dear readers,

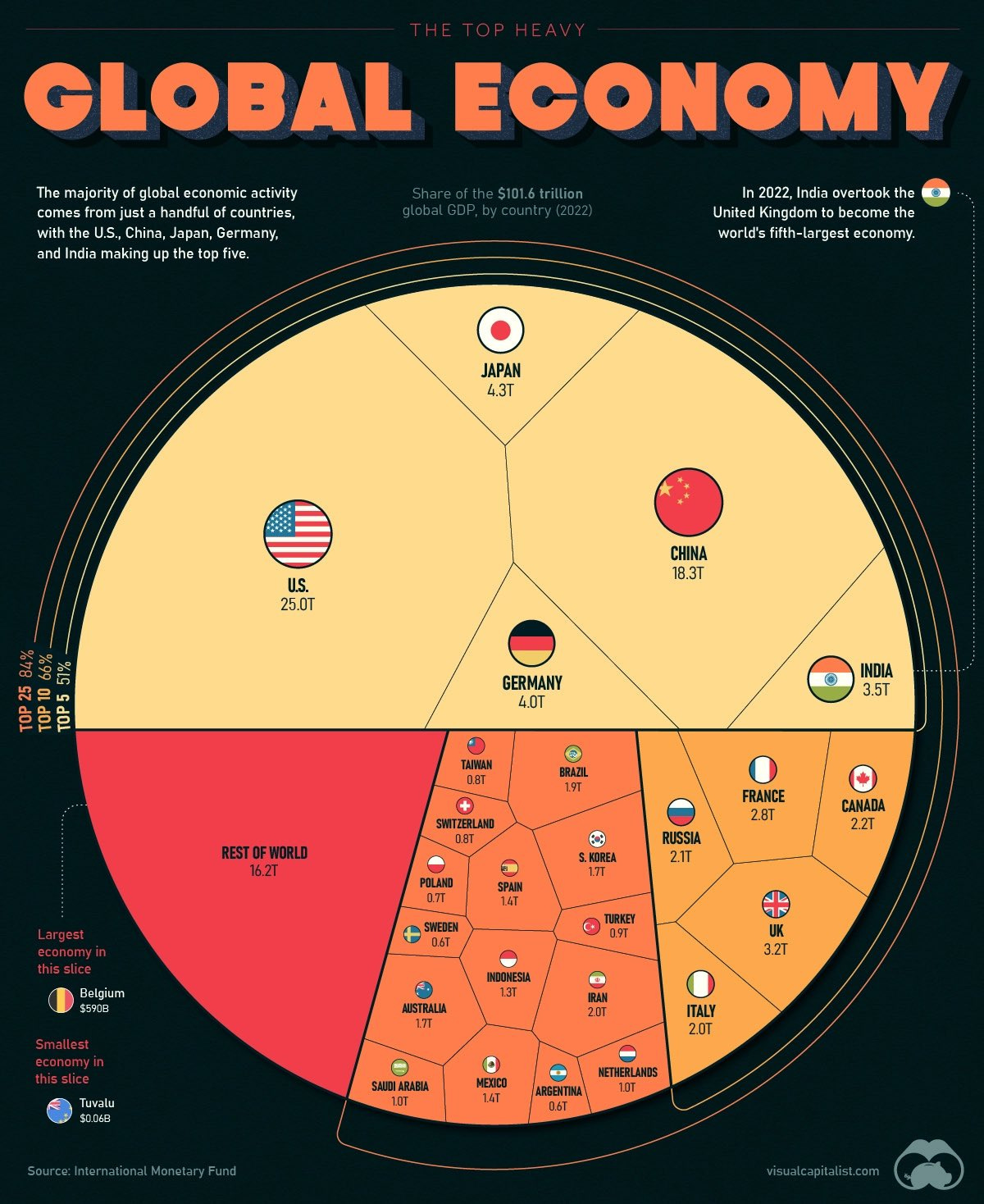

today we are going to focus on India, a 3,000-year-old civilization that has fascinated me for many years. The country is hosting the G20 summit this weekend, bringing together the heads of state of the world's 20 leading economies. Despite the numerous challenges it faces, the Asian giant is currently experiencing a symbolically prosperous period: with the moon landing of its Chandrayaan-3 probe, it has just entered the very exclusive club of countries having placed a machine on the moon (with the US, China and the USSR); its economy has become the 5th in the world, surpassing UK; and India is now the most populous country in the world with its 1.425 billion inhabitants, overtaking China.

The country has been led since 2014 by Narendra Modi, the leader of the BJP1 party (Bharatiya Janata Party or “Indian People’s Party”), the Indian right. Popular, he seems well on his way to being re-elected in 2024 for a third 5-year term. With India poised to take a leading position on the global stage in the decades to come, I wanted to better understand how Indian leaders see the world. This is why I read The India Way, Strategies for an Uncertain World, a book written in 2020 by Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, one of the most influential ministers in the Modi government. Diplomat with a prestigious career (he notably served as India's ambassador to China and the United States), Jaishankar has served as the country's Minister of External affairs since 20192.

The book offers an overview of the challenges India is facing in the 21st century and clarifies the goals of its ruling elite. Four main ideas can be identified:

Economic development: an absolute priority

The India time?

The relationship with China: the frenemies

The pride of a civilization: an India that is now more Bharat

1. Economic development: an absolute priority

For the author, strengthening the Indian economy is a priority: the country wants to have the means to achieve its ambitions. An interesting point is the way in which the Covid-19 crisis is being treated: beyond the global health shock, the minister especially deplores its impact on the prosperity of the country. By slowing growth, the pandemic has slowed the pace of exit from poverty: “Many, not just in India, who would have otherwise come out of poverty will have to wait longer”. 415 million Indians emerged from poverty between 2006 and 2019 according to the UN but 10% of the population still lives on less than $2 per day. Modi has set a clear objective for the country: in 2047, for 100 years of its independence, India must be a developed and “poverty free” economy.

However, the author notes that economic emergence will be more difficult for India than for China: his country will not benefit from the level of openness of economic exchanges of the 2000s and 2010s which allowed China to multiply per ten its GDP per capita in 20 years (from $1,000/cap. in 2000 to $10,000/cap. in 2020). India will have to emerge into a more conflictual and less open world.

2. The India time?

“In dealing with the West, the Chinese often invoke a century of humiliation to justify their positions now. But if anybody should be complaining, it should be India which saw two – not one – centuries of rape and pillaging by Europe.”

After recalling the colonial era, S. Jaishankar devotes a significant part of his book to Indian nationalism. Regarded very negatively in Europe, the author sees, on the contrary, nationalism as the ideology which made it possible to free India from colonization. He affirms that nationalism is a positive force contributing to social cohesion and the influence of the country. The author insists: “a nationalistic India is willing to do more with the world, not less”. Indian nationalism, heir to an ancient and pluralistic civilization, is not synonymous with self-closure: for Jaishankar it is a positive force aimed at maximizing the capacities of a country to actively engage in international scene.

Regarding international relations, the minister advocates for a strategically autonomous India, not dependent on any alliance. Thus, even if the country is a privileged interlocutor of Westerners in Asia who see it as a counterweight to China, it continues to trade with Russia at the same time. It is the application at the diplomatic level of the concept of Atmanirbhar Bharat (autonomous India), promoted by Narendra Modi since his first election in 2014. The objective is to build a resilient economy tending towards self-sufficiency in key areas (military, pharmaceutical or food). It is also part of the Indian tradition: in 1909, under the British Raj, Gandhi published Hind Swaraj3, which could be translated as: “the fact of being one’s own sovereign”.

Note that France is seen as a faithful partner by the minister: beyond the recent sale of Rafales jet, the unfailing French support for the Indian nuclear tests of 1998 -allowing the country to acquire atomic weapons- has not been forgotten.

3. The relationship with China: the frenemies

“The ability of India and China to work together could determine the Asian century. Equally, their difficulties in doing so may well undermine it. Given this combination of promise and challenges, their ties are without doubt one of the most consequential relationships of our times.”

India and China are key players in the 21st century and the state of their relationship is of crucial importance to the future of Asia and the world. In the West, we are used to pitting the two Asian giants against each other, playing democratic India against authoritarian China. Certainly the minister does not hide the competition that exists between the two countries: China is a geopolitical and economic rival, as proven by the ban on Chinese applications in India (Tik Tok for example) or the recurring skirmishes at the Sino-Indian border. However he believes that if his country and China can come to an agreement, they could reduce Western influence and define new rules for organizing international relations.

4. The pride of a civilization: an India that is now more Bharat

“As Indians prepare for greater contributions, they must rely on their own traditions to equip them in facing a tumultuous world. That is certainly possible in an India that is now more Bharat4”.

India sees itself as a civilization-state and the author of The India Way encourages Indians to draw inspiration from their rich centuries-old heritage. He sets an example: to conduct foreign policy, the minister says he draws inspiration from the Mahabharata5, sacred text of Hinduism and great mythical story known to all Indians which plays in the country the role that the Iliad and the Odyssey and the Bible were able to play in the West. “The Mahabharata”, writes the author, “is indisputably the most vivid distillation of Indian thoughts on statecraft”: for example, he sees in the Bhagavad-Gita (the most famous part of the story in which a warrior hesitates to carry out his duty) an incentive “to implement key policies without being discouraged by the collateral consequences of the action.”

My take: the Indians want to make up for lost time

By finishing this book, we better understand the state of mind of Indian leaders: for the 21st century, they aspire to a prosperous India, proud of its civilization and playing a leading role on the world stage. This desire to make up for lost time is often mixed with a quest for recognition and sometimes a feeling of revenge. This determination and this strong civilizational consciousness contrast with a Europe tempted by degrowth and uncomfortable with its own cultural heritage.

For the author, the West should not have any illusions about its special relationship with India. If the Asian giant is building strong partnerships with the West and in particular with the United States, it is because the country today finds an advantage (technology transfer, economic development). But ultimately, the objective remains the autonomy of India and only the country's interests will prevail.

With 100 million members, it is the largest party in the world.

He is also the brother of Sanjay Subrahmanyam, recognized historian and professor at the Collège de France.

Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule, work written by Gandhi in 1909 in which he sets out his ideology. We will definitely talk about this in a future article.

Bharat is the ancient name of India, in Sanskrit.

The Mahabharata is described by the French novelist and screewriter Jean-Claude Carrière in his Dictionnaire amoureux de l’Inde (Loving dictionnary of India) as “the invisible cement that makes of so many peoples a people”. Remember that the Indian Constitution recognizes 22 official languages (Hindi, Tamil, Bengali, Gujarati, etc.).